The Whipping Post of Kanawha County,

West Virginia

By Tom. Swinburn

Strolling into the rooms of the West

Virginia Historical Society one day, I had a pleasant chat with

its venerable president, in which he called my attention to the

stump of the old whipping post there preserved. This recalled

what I had heard of the last man whipped at the post. He

requested me to write a sketch about it for the Magazine.

Not satisfied to depend on my own

recollections, which were but second-hand at best, nor even on

the memories of those yet remaining who were cognizant of the

events related. I searched the county records at such odd

intervals as I could spare from other duties chiefly at the noon

hour.

I wished to present a complete and

accurate history of the post and some account of each whipping.

But though the number of punishments was not great, I found the

limited time at my disposal utterly inadequate to the task. I

got such assistance from old citizens in regard to persons who

had been whipped as their memories could furnish. Then I went to

the records of the county, but found the older ones without

indexes, which of course made the task the harder.

As to the incidents of the last legal

whipping at the Kanawha post, I had the assistance of Mr. A. P.

Fry, Col. John Clarkson, Hon. Jacob Goshorn and others.

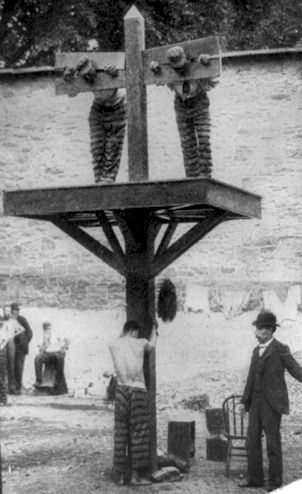

The Kanawha whipping post is supposed

to have been set up about the time when the brick court-house

was built. This was in the year 1817. But I doubt if the piece

now in the Society's room could have lasted so long. It was more

than a mere post. It was probably 18 feet high. I was divided

into two stories by a platform. On this platform, reached by

steps or ladder, stood the culprits condemned to the pillory.

There was room for two. This pillory was made by passing two

stout planks through a slot in the post, on edge, one above the

other. Holes were made in the planks to receive the necks and

wrists of the criminals, one on either side of the post. The

slot in the post was of sufficient length to let the upper plank

be raised to admit the heads and hands of the victim, then it

was let down and secured by a wedge-shaped key which locked them

fast and utterly helpless against the pelting's of mischievous

men and boys.

The whipping was done under this

platform. The condemned one stood on the ground, his arms round

the post, his wrists strapped to staples in the post. The number

of lashes varied with the enormity of the offense, and the

temper of the judges. The severity of the infliction was with

the officer who administered it. In one instance I found in the

record, the sheriff was directed to see the number of lashes on

the culprit's bare back "well laid on." And I am told that one

application affected a cure, so that a man was hardly ever, or

never known to incur the punishment a second time. This leads

many persons to regret the abolition of the post, and advocate

its return. The following article from The Literary Digest of

last December 13 voices the public sentiment for and against.

The article is entitled:

The Whipping Post in Delaware

The survival

of the whipping post in the State of Delaware, and the recent

flogging of a fourteen year old boy for petty theft, has aroused

some discussion in the press as to the efficacy of this method

of punishing crime. In the opinion of the New York Journal, the

practice is a "relic of barbarism" and belongs to the days of

the 'thumb-screw and rack. "Only Delaware," it says, "has

continued to enforce this degrading law, in defiance of progress

and the sentiment of other States of the American sisterhood and

it calls upon this State to put an end to the 'hideous

anachronism before the dawn of the new century. On the other

hand, the Washington Post expresses the belief that in cases of

hardened crime, such as incorrigible viciousness, wife beating,

etc. the effect of the "cat-o-nine-tails" is most salutory. It

continues:

"Every

rational observer in this direction knows that for such monsters

there is no deterrent save plain and simple physical suffering.

The so called humane and civilized methods have been tried and

found wanting. The brute goes to jail, fares sumptuously every

day, while his wretched family suffer cold and hunger, and in

almost every instance returns with unabated energy to the

practice of his favorite cruelty. For such beasts as these the

whipping post is the only adequate prescription. They are open

to no argument less eloquent than the lash. They fear this as

they fear nothing else. And if the custom were adopted and

rigidly enforced in every city, town, and neighborhood

throughout the land, the ends of Christian mercy would be better

served."

Harpers

Weekly (New York), looks at the matter in the same light,

declaring that "a good whipping administered in private would

probably be more effective as a preventative than a period of

comfortable sequestration upon the banks of the Hudson River or

in any other of the first-class criminal hostelries of the

country." Now it seems to me that if punishment is intended to

deter crime that form which does deter would be the proper one

to adopt. True, the whipping post is a relic of barbarism. But

is not every kind of physical punishment barbarous? Have we not

derived the practice of inflicting physical pain upon offenders

from our barbarian ancestors? What is more clearly barbarous

than dangling a man or woman by the neck at the end of a rope

till strangled to death? Why do we not abolish all relics of

barbarism in modes of punishment, such as the ball and chain,

the water hose, etc.? Because, like out barbarian forefathers we

believe the fear of pain the best deterrent. On this principle

the best deterrent is that which criminals most fear, and I

believe the fear of whipping is more effectual than any other.

But I am in

favor of removing all barbarous punishments. Yet, it were better

to remove the need of punishment than the instrument. The

instrument will inflict no pain if not used. The instrument will

not be used if there be no need. There will be no need if the

cause be removed. And is not the law-breaker the cause? Partly,

but more than he the law-maker. I shall hardly be understood

here. But under the term law I mean not only, statutory law, but

that wider and stronger law, public opinion and social custom.

Not to be tedious, I hold that our civilization fosters

millionaires and paupers, philanthropists and criminals. The

paupers and criminals far outnumbering the former. The pauper

may be to blame. Civilization always is. The criminal is

probably to blame. Civilization certainly is. But to my story.

Sometime in

the thirties Col. Andrew Donnally visited the city of

Philadelphia, and there found a young Irishman named Arthur

Mowbry, who as was customary in that day, had secured his

passage to this broad land of freedom and plenty under a

contract to hire himself out to someone who should pay the

amount of his passage, and be repaid by the services of the

immigrant. Being a voting man of parts. Col. Donnally, who was

himself an Irishman, took a fancy to him paid his passage, and

brought him to Kanawha. Here he became a general favorite, lived

in the family of Col. Donnally, and was treated as a member of

it. He served as clerk in the store of his employer, and had a

fair prospect of success in life. But he seems to have become

vain, fond of the company of other young men and of dressing

beyond his means. He took to drinking too much, and lost favor

with his patron, and eventually forged an order on Lewis

Rutliner & Co., which eventually landed him in the penitentiary.

But he did not remain there long for his counsel, Jacob Goshorn,

took an appeal in his case and reversed the Circuit Superior

Court, and brought his client hack to Kanawha. The whipping was

not for this forgery, but seems, some of my informants thought,

to have grown out of it in this way:

Mowbray, (his

name is spelled in various ways) and some boon companions had a

sort of club room where they spent their leisure time. In the

free and easy life they led they thought nothing of wearing each

other's clothes. Now it appears by the county records that the

first indictment against Mobray was quashed on some technical

defect. Perhaps thinking that would be the end of it, and not

willing to let him off so easily, my informants are of opinion

that a charge of stealing the coat of one Samuel Hickock, one of

the boon companions, was trumped up against him, and for this he

was whipped. Unfortunately for this theory the indictment for

stealing was examined a month before the examination for

forgery: The charge of stealing, however, may have been held

back to see the result of the charge of forgery, and when that

was quashed this was pressed. At any rate he was whipped for

stealing the coat. I have not been able to ascertain who did the

whipping. Col. Clarkson thinks it was Wm. Hatcher, deputy

sheriff, who was severe. Mr. Goshorn thinks it was John Slack,

and thinks he did it early in the morning when there were no

spectators, and that it was very lightly given.

West

Virginia AHGP

Source: The West Virginia Historical Magazine Quarterly,

Charleston West Virginia, 1901.

|